The Forced Retirement of Lord Denning

How the growth of multiculturalism in Britain led to the forced retirement of one of Britain’s greatest judges

On the 3rd October 1995, OJ Simpson was acquitted of murder. His ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ron Goldman, had been brutally hacked to death, with several wounds apiece. Simpson’s blood was all over the crime scene. His victims’ blood was found in his car and in his home. Simpson had fresh cuts on his hand, did not enquire how his ex wife had died when notified, and was placed by witnesses at crucial scenes. No other participant’s DNA was found there. The evidence for Simpson’s guilt was overwhelming, but the jury acquitted him unanimously.

Opinion polls taken during and immediately after the trial pointed to a serious schism in American culture. White Americans were overwhelmingly likely to believe that Simpson was guilty; Black Americans overwhelmingly thought the opposite. The 328 day trial had acted as a magnifying glass to America's issues: racist cops; domestic violence; divided communities. By the time the jury retired to reach a verdict, a fever had gripped America. The verdict became a public spectacle. Cameramen camped outside of demonstrations, inside college dormitories, on the streets. Oprah Winfrey filmed a special episode that featured a live reaction from her (female, middle class) audience. View any of these images, watch any of these interviews, and the divide is stark: African Americans are jubilant, white Americans horrified. The trial had become a symptom of the racial division in 90s America. In the 30 years since the trial the racial gap has narrowed, as Simpson’s celebrity status has diminished, but it was palpable at the time.

Both sides in the trial knew that the result would hinge on race. Defence and prosecution made full use of their right to ‘peremptory challenge’ the participants on the jury in order to produce one favourable to their case. In the end, the 12-person jury ended up being 75% black and 25% white. After 10 months of trial, the jury deliberated for a total of four hours before acquitting Simpson. One member, himself a former Black Panther, gave Simpson the Black Power salute as he left the courtroom.

Reliability of Juries

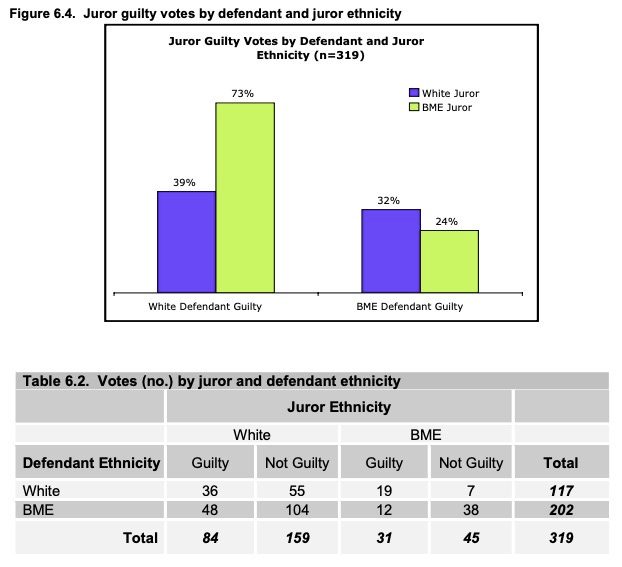

We don’t like to consider the possibility that juries may make judgements on criminal cases based on their racial, religious, ethnic, or cultural composition, rather than the evidence before them. The privacy required of jury deliberations, and the injunctions which are imposed on discussing deliberations after the fact, inhibit effective analysis of whether this occurs. Yet the limited work which has been done in this area demonstrates that race has become a relevant factor in determining verdicts. A 2007 report from the Ministry of Justice determined that there was evidence of a racial split in the likelihood of different jurors convicting or acquitting in a series of simulated experiments.

The MOJ report characterises this as evidence of “same-race leniency”, but white jurors were actually more likely to find a white defendant guilty than they were a BME (black and minority ethnic) defendant - though conviction rates were similar for both (39% and 32%). The huge gulf is between BME jurors when reviewing a white or a BME defendant, where the conviction rate ranges considerably (73% to 24%). When looking specifically at ABH (actual bodily harm) cases, the study discovered that white jurors had low conviction rates for both white and BME defendants (35% and 27% respectively). By contrast, BME jurors had a high conviction rate for the White defendant (71%) and a low conviction rate for the BME defendant (17%).

Jury trial operates successfully in a homogenous society, where all participants have an equally vested interest in upholding and enforcing the law, and treating the defendant as an individual rather than a member of a group. As soon as jurors approach cases, not in terms of guilt and evidence, but in terms of ‘sides’, then the whole system is undermined. In 1982, the long-serving Master of the Rolls Lord Denning was forced to retire for making precisely this prediction.

Lord Denning

Alfred Thompson ‘Tom’ Denning (1899 - 1999) was an English institution. He was the last of the Victorians who fought in the trenches of the First World War to still be involved in public service during the Thatcher era. Called to the Bar in 1923, he was appointed a High Court Judge in 1944, and rapidly progressed through appointments to the Court of Appeal (1948) and the House of Lords (1957). Denning was an idiosyncratic member of the Judiciary. He was more than willing to find an obscure precedent to ensure that justice be done - and equally willing to disregard existing precedents and even the wording of statutes for the same end. His individual style made the House of Lords a cramped and confining experience for him, and in 1962 he gratefully accepted the position of Master of the Rolls - head of the Civil Division of the Court of Appeal. Although the court ranked below the House of Lords, his role gave him greater scope for applying his own interpretations to the cases before him.

His idiosyncrasies extended to questions of personal style. Lord Denning is the only judge whose judgements are read as much for their literary value as for their legal importance. It’s impossible to quote any without wanting to quote more, but as a brief selection: “It happened on April 19, 1964. It was bluebell time in Kent.”; “In summertime village cricket is a delight to everyone. Nearly every village has its own cricket field where the young men play and the old men watch.”; “This is a case of a barmaid who was badly bitten by a big dog.”; “Broadchalke is one of the most pleasing villages in England. Old Herbert Bundy, the defendant, was a farmer there. His home was at Yew Tree Farm. It went back for 300 years. His family had been there for generations. It was his only asset. But he did a very foolish thing. He mortgaged it to the bank. Up to the very hilt.”

Lord Denning’s fame partly derived from his report on the Profumo affair; the first government report to be a best-seller since Beveridge. His old fashioned moral conservatism, and his defence of the individual against government, commercial, or trade union power ensured his popularity. In the late 1970s, as ill health inhibited Lord Denning and his wife from travelling as extensively as they had previously done, he decided to turn his leisure time to writing books on the current state of English law. These were well received, until the publication of What Next in the Law (1982) opened up the invidious question of the viability of juries in a multicultural society.

The Forced Retirement

Denning’s What Next in the Law proceeded in the typically staid manner of a book on English law, beginning with a review of some of the great legal reformers in English history: Bracton, Coke, Blackstone, Mansfield, Brougham. He then provided a survey of several elements of English law, such as libel and legal aid, identifying where the law currently stood and suggesting proposals for reform. In his section on jury trial, Denning took issue with the right of peremptory challenge, by which a defendant could object to the presence on the jury of up to three jurors without cause (it had been seven prior to 1977). Denning referenced a trial which had followed the Bristol riots of 1980. He had earlier made reference to this same issue in his Mansion House speech of 1981:

“Let me tell you of the riots in Bristol. It was a coloured area. A few of the good Bristol police force went to inquire into some wrongful acts being committed there, They were set upon by coloured people living there. Much violence. Much damage. Twelve of them were arrested and charged with riot - a riot it certainly was. So they were tried by jury. There were 12 accused. Each had three challenges. That is 36 altogether. The accused challenged the white men, but not the coloured men, nor the women. Eight were acquitted. On four the jury could not agree. The prosecution proceeded no further. The cost was £500,000. This was, in my opinion, an abuse of the right of challenge, to get a jury of their own choice.”

This speech attracted little attention at the time Denning delivered it, but in What’s Next in the Law he returned to the theme:

“It was done so as to secure as many coloured people on the jury as possible - by objecting to whites. This meant that five of the jury were coloured and seven white. The evidence against two of the accused was so strong that you would think they would be found guilty. But there was a disagreement.

The underlying assumption is that all citizens are sufficiently qualified to serve on a jury. I do not agree. The English are no longer a homogenous race. They are white and black, coloured and brown. They no longer share the same standards of conduct. Some of them come from countries where bribery and graft are accepted as an integral part of life: and where stealing is a virtue so long as you are not found out… They will never accept the word of a policeman against one of their own.”

Denning didn’t argue that minorities should be excluded from sitting on juries, but suggested that all potential jurors of all races should only be allowed to serve if they had proved themselves “sensible and responsible members of the community.” This had always been a basic principle of English law, and prior to 1974 there had been a property qualification for eligibility to sit on a jury.

These remarks would come to dominate the popular understanding of Lord Denning and his work and are always quoted as though they are necessarily outrageous and ugly. There was widespread condemnation of his words, which by 1982 were deeply unfashionable. The Scarman Report had been published in November 1981, and the principles of state-sponsored multiculturalism were already firmly embedded in British society. The jurors who had sat on that trial understandably felt that their integrity was being questioned, and immediately suggested that they would bring a libel action. The book was recalled, pulped, and reissued (my version doesn’t have the offending passages). Denning apologised to the jurors he had offended, and announced that he would shortly retire. He was 83 at the time, and had only remained on the Bench because he had become a Judge prior to an age limit of 75 being imposed.

Denning’s comments were ill-judged, because he was making specific references to particular people in an identified case. Yet, despite the obloquy which he received, was he actually wrong? Other cultures do have differing attitudes to bribery, group identity, and the relationship between public law and family dynamics. Denning transgressed by speculating about individuals whom he did not know. Yet the nature of our jury system is such that it is extremely difficult to conduct any proper analysis of how they work in practice, and how well they operate in a multicultural environment.

Trial by jury is one of the most crucial civil liberties which England has historically enjoyed. Like much else in our common law tradition, our systems were effective in a high trust society with a strong and shared moral consensus. Our democracy works, because historically we were a single demos. The pattern of mass immigration in this country has undermined the natural homogeneity of the population. In the MOJ’s 2007 study (Diversity and Fairness in the Jury System), it was reported that South Asians had more confidence in a judicial decision if another South Asian had been involved in it, even when no there was no evidence of any bias. Yet it is clearly impossible for us to engineer every trial to ensure that perpetrators are demographically paired with that day’s magistrate. This also raises the further question of why we should have engaged in a demographic transformation so radical that - rather than the perpetrator - it is our judicial system which is being placed in the dock. I argued in ‘Brezhnev-era Liberalism’ that one reason for the sclerotic thinking of our political class is that they have failed to update their analysis in the light of what their policies have actually produced: I don’t remember anyone making the case to the British people that we ought to engage in mass immigration, but that our basic trust in judicial integrity would be jeopardised as a necessary trade-off.

Mass immigration has undermined the basic coherence of our nation. Had the numbers been small, and had we retained civilisational confidence, then newcomers could easily have been assimilated to the existing culture. We are not America, and have never needed to deal with the embedded racial problems which exist in that society. But the sheer scale of inbound migration has inhibited the processes of integration and assimilation which would have otherwise occurred. Lord Denning was often dismissed as an old-fashioned Edwardian who had failed to keep up with the times. Crude though his language was, time is likely to prove that it was Lord Denning who had a much better understanding of the world we have built for ourselves, and his opponents who were still naively living in an Edwardian idyll.

That MoJ report is amazing. Crazy this has been known officially for nearly 20 years.

Thanks for the article. Despite studying law and now practicing as a solicitor I had forgotten about some of the Denning controversies in his later career. Some rambling thoughts with no particular agenda:

- the example Denning cites back in the 80s is an interesting one, because I suspect the black Bristol jury members would have been largely of Afro-Caribbean descent, and well integrated by most people’s standards (English born/speaking, at least nominally Christian etc), but still decided to return an incorrect verdict due to racial biases/perceived injustices in the system. An interesting question is why they perhaps felt that way, and what the experiences of their community were to date which led this. The answer is probably more complex than Denning’s initial observations;

- though the statistics cited are very interesting (though a little out of date) and do indicate the potential for bias, I suspect there are also many other points of prejudice which may also influence a juror’s decision which aren’t based on race and are probably more common;

- we still obviously get incorrect jury decisions from white juries. I might be wrong but I’m pretty sure the Colston Four riots verdict was delivered by a largely white jury. Which perhaps raises bigger questions around how different moral and cultural values now permeate our public discourse, which aren’t particularly linked with mass migration.

I think the point you raise about beefing up the requirements for doing jury service is a good idea. But personally I’m not sure if the mass migration problem is one which has (yet) caused problems re incorrect jury verdicts.